Thinking, Fast and Slow (2011) summarizes the decades of research that led to Kahneman’s Nobel Prize, highlighting his contributions to psychology and behavioral economics. His research has improved our understanding of decision-making, common judgment errors, and self-improvement through understanding and addressing these issues.

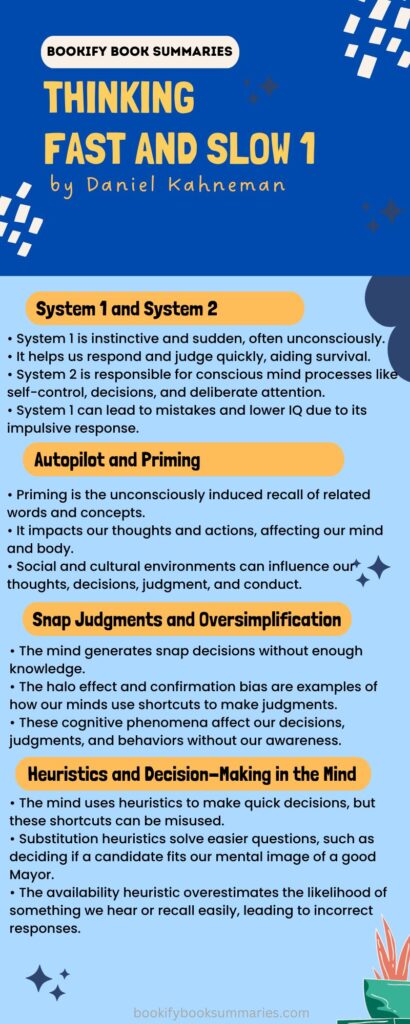

Imagine a story between two characters ‘Impulsive, instinctive, intuitive System 1’ and ‘careful, deliberate, calculating System 2’ They influence our thoughts, judgments, and behaviors as they interact.

System 1 works instinctively and suddenly, often unconsciously. This technique works when you hear a loud, unexpected sound at work. You do what? The sound undoubtedly quickly catches your attention. That’s System 1.

Our evolutionary past gave us the ability to respond and judge quickly, which helps us survive.

When we imagine the brain region responsible for our decisions, thinking, and beliefs, we think of System 2. Self-control, decisions, and deliberate attention are conscious mind processes.

Say you’re hunting for a woman in a throng. Your mind concentrates on recalling the person’s traits and anything that would assist you find her. This concentration eliminates distractions, and you barely see others in the crowd. If you stay focused, you may discover her in minutes, but if you become distracted, you may not.

Table of Contents

ToggleA lethargic mind can make mistakes and lower IQ.

Solve this famous bat-and-ball issue to compare the two systems:

Bat and ball cost $1.10. The bat costs $1 more than the ball. The ball costs how much?

System 1 was intuitive and automatic, so you probably thought $0.10, which is erroneous! Please do the math now.

Do you see your error? Correct answer: $0.05.

You answered intuitively because your impulsive System 1 took over. But it replied too quickly.

The bat-and-ball dilemma tricks System 1, which usually calls on System 2 to solve problems it doesn’t understand. It thinks the situation is easier than it is and thinks it can manage it alone.

We’re mentally lazy, as the bat-and-ball conundrum shows. When using our brain, we use the least energy feasible for each activity. This is the law of least effort. When it feels it can get away with System 1, our mind won’t check the response using System 2 because it uses more energy.

This carelessness is bad because System 2 is crucial to our intelligence. System-2 skills like focus and self-control boost intellect, according to research. Our thoughts could have checked the answer using System 2 to avoid this typical blunder in the bat-and-ball problem.

Autopilot: why we sometimes act without thinking.

The word fragment “SO_P” evokes what? Probably nothing. What about “EAT” first? When you reread “SO_P,” you probably spell it “SOUP.” This is priming.

Exposure to a term, concept, or event primes us to recall related ones. If you had read “SHOWER” instead of “EAT” above, you would have probably written “SOAP.”

Priming impacts our thoughts and actions. Hearing specific words and notions affects the mind and body. A study indicated that subjects primed with geriatric phrases like “Florida” and “wrinkle” walked slower than usual.

Amazingly, we prime actions and thoughts unconsciously.

Priming illustrates that, despite popular belief, we are not always in control of our behaviors, judgments, and choices. Instead, social and cultural environments prime us.

Kathleen Vohs found that money motivates individuals. Exposure to money pictures makes people more independent and less ready to depend on or accept demands from others. According to Vohs’s research, living in a society with prime money cues may discourage compassion.

Priming, like other societal factors, can influence an individual’s thoughts, decisions, judgment, and conduct, which reflect back into the culture and greatly influence our society.

Snap judgments: how the mind generates snap decisions without enough knowledge.

Imagine meeting Sam at a party and getting along with him. Later, someone asks if you know anyone who could donate to their organization. Even though you do not know anything about Sam still you think of him.

Since you enjoyed one part of Sam, you figured you would appreciate everything else about him. Even without knowing much about someone, we typically approve or dislike.

Our mind’s tendency to oversimplify without enough information causes judgment errors. The halo effect, or enhanced emotional coherence, occurs when you cast a halo on Ben while knowing nothing about him because you like his approachability.

Our thoughts utilize other shortcuts while formulating judgments.

Confirmation bias is the tendency to agree with information that supports existing ideas and accept proposed information.

Asking “Is Dave friendly?” shows this. Studies demonstrate that when asked this question without other information, we automatically think James is friendly since the mind validates the idea.

The halo effect and confirmation bias result from our eagerness to judge. But we don’t always have enough evidence to make an appropriate call, therefore we make mistakes. Our minds use misleading ideas and oversimplifications to fill data gaps, leading to possibly incorrect judgments.

These cognitive phenomena affect our decisions, judgments, and behaviors without our awareness, like priming.

The mind employs heuristics to make speedy conclusions.

We often must make snap decisions. Our minds have created shortcuts to help us understand our surroundings quickly. These are heuristics.

These processes are usually helpful, but our minds abuse them. We can make blunders by applying them to unsuitable contexts. We can look at the substitution and availability heuristics to see what they are and how they can cause problems.

Substitution heuristics solve easier questions than the original ones.

Example: “That woman is a candidate for Mayor. Will she do well in office? We reflexively answer “Does this woman look like a good Mayor?” instead of the original question.

Instead of investigating the candidate’s biography and policies, we ask ourselves if she fits our mental notion of a good Mayor. Despite her years of political experience, we may reject her if she doesn’t suit image of mayor formed in our mind.

Next, the availability heuristic overestimates the likelihood of something you hear often or recall easily. Strokes kill more people than accidents. Accidental fatalities are more common in the media and leave a bigger impression on us than stroke deaths, so we may respond incorrectly to them.

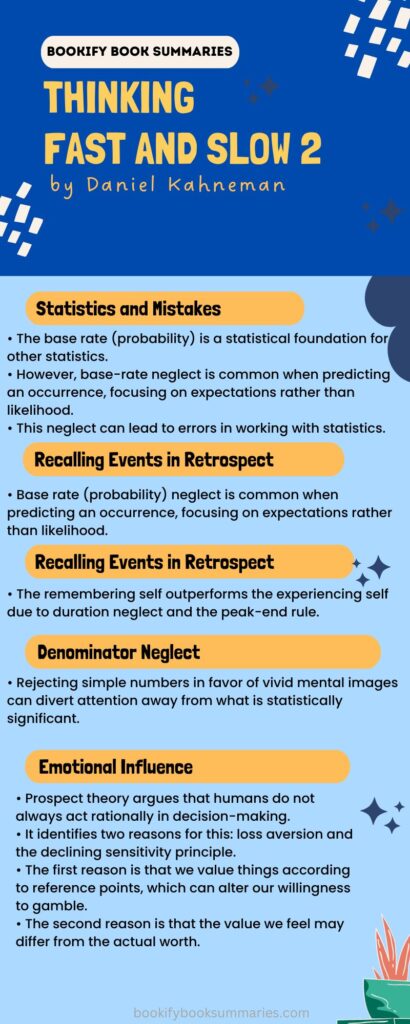

why we struggle with statistics and make mistakes.

Considering the base rate (probability) can help. This is a statistical foundation for other statistics. Suppose a taxi firm has 20% yellow and 80% red cabs. Yellow taxis have a 20% probability and red cabs an 80% probability. Keep in mind the probability when ordering a cab and you can guess its color to fairly accurate degree.

We should constantly recall the base rate when predicting an occurrence, but we don’t. In fact, base-rate neglect is widespread.

We ignore the base rate since we focus on expectations rather than likelihood. Consider those cabs again: If five red cabs pass by, you might think that next one will be yellow. If we recall the base rate, the probability that next cab will be red is still 80 percent no matter how many of yellow ones pass by. However, we focus on the expected yellow cab and do mistakes.

Working with statistics often involves base-rate neglect. Remembering that everything regresses to the mean is important. This acknowledges that all situations have an average and will eventually return to it.

For instance, if a football striker who averages five goals per month achieves 10 goals in September, his coach will be thrilled, but if he scores five goals per month for the rest of the year, his coach will likely reprimand her for not continuing her “hot streak” This criticism is unfair to the striker, who is merely regressing to the mean!

Why we recall events in retrospect rather than from firsthand experience.

Our minds do not remember experiences in a straightforward manner. We have two distinct mechanisms called memory selves, each of which remembers situations differently.

First, there is the experiencing self, which records how we feel right now. It wonders, “How does it feel now?”

Then there’s the remembering self, which documents how the entire event played out after the fact. It inquires, “How was it on the whole?”

The experiencing self provides a more accurate description of what happened since our emotions throughout an event are always the most true. However, the remembering self, which is less accurate since it records memories after the situation has passed, dominates our memory.

There are two reasons why the remembering self outperforms the experiencing self. The first is known as duration neglect, in which we overlook the entire duration of an event in favor of a specific recollection from it. Second, we have the peak-end rule, which emphasizes what happens at the end of an event.

This experiment measuring people’s memories of a painful colonoscopy exemplifies the power of the remembering self. Before the colonoscopy, the patients were divided into two groups: those in one group received long, drawn-out colonoscopies, while those in the other were given considerably shorter procedures, but the level of pain increased near the conclusion.

You’d imagine that the most dissatisfied patients would be those who went through the longest treatment, as their suffering lasted longer. This is certainly how they felt at the time. When questioned about their pain during the treatment, each patient offered an accurate answer: those who had longer procedures felt worse. However, after the event, when the remembering self gained control, those who went through the shorter procedure with the more painful ending felt the worst. This survey provides a convincing demonstration of duration neglect, the peak-end rule, and our poor recollections.

How changing our focus may change our ideas and actions.

Our minds expend varying quantities of energy depending on the work. When there is no need to mobilize attention and minimal energy is required, we are in a state of cognitive comfort. However, when our minds need to mobilize attention, they expend more energy and enter a condition of cognitive strain.

These fluctuations in the brain’s energy levels have a significant impact on how we behave.

In a condition of cognitive comfort, the intuitive System 1 takes control of our thinking, while the logical and more energy-demanding System 2 is weak. This means that we are more perceptive, creative, and happy, but we are also more prone to making mistakes.

In a situation of cognitive pressure, our awareness is increased, and System 2 takes over. System 2 is more prepared to double-check our decisions than System 1, thus even if we are significantly less imaginative, we will make fewer mistakes.

You may actively control the amount of energy the mind expends to get into the correct frame of mind for specific tasks. To make a message more convincing, consider improving cognitive comfort.

One method to accomplish this is to subject ourselves to repetitious information. Information that is repeated or made more remembered becomes more compelling. This is because our minds have evolved to respond positively when regularly exposed to clear messages. When we perceive something familiar, we experience a level of cognitive ease.

Cognitive strain, on the other hand, helps us succeed at tasks such as statistical analysis.

We can achieve this state by exposing ourselves to information presented in a confusing manner, for as through hard-to-read text. Our minds wake up and increase their energy levels in an attempt to understand the situation, making us less likely to simply give up.

How probabilities are given to us influences our risk perception.

The manner in which ideas and problems are presented to us has a significant impact on how we evaluate them. Slight changes in the details or focus of a statement or question can have a significant impact on how we respond to it.

The way we assess risk is an excellent example of this.

You may believe that after we have determined the likelihood of a danger occurring, everyone will address it in the same manner. However, this is not the case. Even with precisely calculated probabilities, simply changing the way the figure is expressed can alter how we approach it.

People, for example, will perceive a rare event as more probable to occur if presented in terms of relative frequency rather than statistical likelihood.

The Mr. Jones experiment asked two sets of psychiatric doctors if it was safe to release Mr. Jones from the psychiatric institution. The first group was informed that patients like Mr. Jones had a “10 percent probability of committing an act of violence,” whereas the second group was informed that “of every 100 patients similar to Mr. Jones, 10 are estimated to commit an act of violence.” The second group had nearly twice as many responders who disputed his release.

Denominator neglect is another method of diverting our attention away from what is statistically significant. This happens when we reject simple numbers in favor of vivid mental images that influence our choices.

Consider the following two statements: “This drug protects children from disease X but has a 0.001 percent chance of permanent disfigurement” and “One of 100,000 children who take this drug will be permanently disfigured.” Even while both statements are equally true, the latter conjures up images of a disfigured infant and is far more persuasive, making us less likely to administer the medicine.

Why we don’t make decisions solely based on rational thought.

How do we as people make decisions?

For a long time, a powerful and respected group of economists argued that we made decisions solely on logical grounds. They contended that we all make choices based on utility theory, which argues that when people make judgments, they look just at the reasonable facts and choose the alternative with the best overall outcome for them, or the most utility.

For example, utility theory would propose the following statement: if you prefer oranges over kiwis, you will choose a 10% chance of getting an orange over a 10% chance of winning a kiwi.

It seems obvious, right?

The Chicago School of Economics and its most well-known scholar, Milton Friedman, dominated this discipline. Using utility theory, the Chicago School contended that individuals in the marketplace made ultra-rational decisions, which economist Richard Thaler and lawyer Cass Sunstein eventually dubbed Econs. As Econs, each human behaves in the same manner, valuing commodities and services according on rational requirements. Furthermore, Econs value their riches rationally, based solely on the benefit it affords them.

Consider two persons, John and Dave, each with a fortune of $5 million. According to utility theory, they have the same wealth, thus they should be equally satisfied with their finances.

But what if we complicate matters a little? Assume their $5 million fortunes are the result of a day at the casino, and the two had dramatically different starting points: John came in with only $1 million and multiplied it, whilst Dave came in with $9 million and lost $5 million. Do you still believe John and Dave are equally satisfied with their $5 million?

Why, rather than making decisions exclusively on rational grounds, we are frequently influenced by emotional aspects.

Kahneman’s prospect theory undermines utility theory by demonstrating that while making decisions, we do not always act rationally.

Consider these two possibilities, for example: In the first scenario, you are awarded $1,000 and must choose between obtaining a guaranteed $500 or accepting a 50% chance of winning an additional $1,000. In the second scenario, you are offered $2,000 and must pick between a guaranteed loss of $500 or a 50 percent chance of losing $1,000.

If we made entirely rational decisions, we would make the same one in both situations. But this is not the case. In the first situation, most people choose a safe bet, whereas in the second case, most people gamble.

Prospect theory explains why this is the case. It identifies at least two reasons why humans do not always behave rationally. Both of these highlight our loss aversion, or the fact that we fear losses more than we appreciate gains.

The first reason is that we value things according to reference points. Starting with $1,000 or $2,000 in the two scenarios alters our willingness to gamble, as the starting point influences how we value our position. The reference point in the first scenario is $1,000, but in the second it is $2,000, so ending up at $1,500 feels like a success in the first but a disheartening loss in the latter. Even if our reasoning is clearly unreasonable, we grasp value based on our starting position rather than the real objective value at the time.

Second, the declining sensitivity principle influences us: the value we feel may differ from the actual worth. For example, dropping from $1,000 to $900 does not feel as horrible as going from $200 to $100, even though the monetary value of both losses is the same. Similarly, in our case, going from $1,500 to $1,000 results in a higher perceived value loss than going from $2,000 to $1,500.

Why does the mind create visualizations to understand the world, but it leads to overconfidence and errors?

Our minds creates detailed mental images to explain ideas and concepts. For example, we have several mental images of the weather. We have a vision of, say, summer weather, which could be of a brilliant, hot sun bathing us in heat.

We use these visuals not only to help us understand things, but also to make decisions.

When making judgments, we look to these visuals and base our assumptions and conclusions on them. For example, if we want to know what clothes to wear in the summer, we base our decisions on our perception of the season’s weather.

The issue is that we put too much trust in these images. Even when numbers and evidence contradict our mental impressions, we continue to let them lead us. In the summer, the weather forecaster may predict somewhat mild weather, but you may still dress in shorts and a T-shirt since that is what your mental image of summer instructs you to wear. You may end up shivering outside!

We are, in sum, immensely overconfident in our frequently incorrect mental pictures. However, there are strategies to overcome your overconfidence and begin making better forecasts.

One approach to avoid mistakes is to use reference class forecasting. Rather than making judgments based on broad mental images, consider specific historical instances to generate a more accurate prediction. For example, recall the last time you walked out on a cool summer day. What were you wearing then?

In addition, you can develop a long-term risk policy that includes particular measures for both success and failure in forecasting. Preparation and protection allow you to depend on evidence rather than vague mental images and generate more accurate projections. In the case of our weather scenario, this could imply packing a sweatshirt simply to be cautious.