Hello, friends! Today, we’ll learn about how the East India Company went from a small room in London to taking over the entire Indian subcontinent from the book The Anarchy by William Dalrymple.

Europeans were different from Mughals. They didn’t want to settle or invest in India. Instead, they focused on trade and markets. Initially, the Dutch were ahead in finding new content and markets, but the English and French soon caught up. The Dutch were mainly focused on the Spice Islands, i.e., Indonesia and Malaysia, while the English and French were more interested in the Indian market.

Formation of the East India Company:

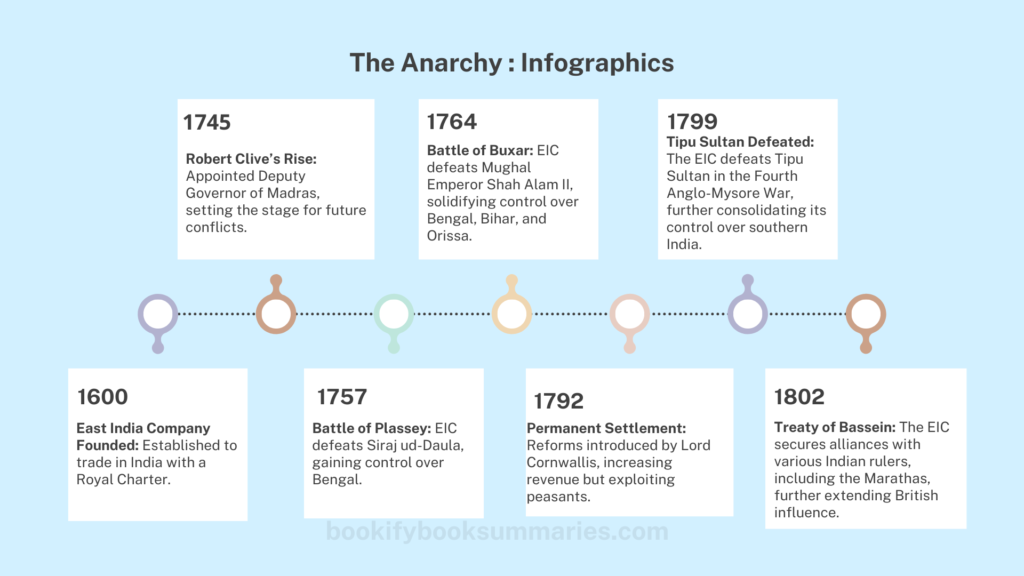

Inspired by the Dutch success, some merchants formed the East India Company in a small room in London in 1600. They received a royal charter from Queen Elizabeth I to trade with the East Indies. At that time, India was under Mughal rule.

The Mughal Empire:

The Mughal Empire started with Babur after the Battle of Panipat in 1526. The last powerful ruler was Aurangzeb, who died in 1707. During this period, the British were trying to establish their presence in India. The first British to land in India was in Surat in 1608.

Early British Struggles:

In 1628, British emissary William Hawkins met with Mughal Emperor Jahangir. Two years later, Sir Thomas Roe spent two years in Jahangir’s court. Due to the vastness of the Mughal Empire, the Company didn’t achieve much success and avoided conflict with the Mughals.

Aurangzeb’s Death and Its Aftermath:

After Aurangzeb’s death in 1707, the Mughal Empire began to decline. The Rajputs and Hindu community, who supported the Mughals, faced suppression under Aurangzeb. His religious fanaticism, jizya tax on Hindus, and desire to expand the empire caused conflicts with the Marathas. After his death, the empire fragmented with various uprisings.

Regional Uprisings:

In the Ganges region, Jats revolted, Sikhs in Punjab, and Marathas in central and western India. Nadir Shah’s attacks further weakened the Mughals. Mughal governors began operating independently, allowing English and French trading posts to grow and private armies to form.

Anglo-French Conflicts:

This period saw the First and Second Carnatic Wars between the English and French, and local rulers. Initially, the French succeeded, but Robert Clive’s leadership turned the tide for the English. Clive, originally an accountant, became a military general and defeated the French, proving European military superiority.

Focus on Bengal:

After establishing dominance in the south, the Company turned its attention to Bengal. The then Nawab, Alivardi Khan, kept the Company at bay. However, his cruel and disliked grandson, Siraj ud-Daula, became the Nawab after Alivardi’s death. Siraj’s distrust and harsh rule led to conflicts with the Company.

Robert Clive’s Return

During this period, Robert Clive was sent back to India due to Anglo-French tensions. Clive planned to take control of Bengal. He initially attacked Siraj’s forces and managed to get back the Company’s properties in Bengal.

Capture of Bengal:

The Company’s army then captured the French post in Chandernagore. Discontent with Siraj’s rule led local merchants and generals, including Mir Jafar, to ally with the Company. They planned to overthrow Siraj, expecting the Company to continue its trade activities.

Battle of Plassey

In 1757, the Battle of Plassey saw the Company’s disciplined forces easily defeating Siraj’s Mughal army. Mir Jafar was installed as the Nawab, marking the first time a joint-stock company became a political power.

Robert Clive’s Departure:

Clive took a large sum of money and returned to London. Warren Hastings was appointed as the Governor of the Company. He strengthened the Company’s administration in Bengal, and its revenues grew.

Internal Conflicts

Internal conflicts among Indian rulers and foreign threats continued to shape the region’s dynamics. Mir Kasim, Mir Jafar’s successor, tried to assert control, leading to conflicts with the Company. In 1764, the Battle of Buxar saw the Company defeating the combined forces of Mir Kasim, Shuja-ud-Daula, and Mughal Emperor Shah Alam II.

The Company’s Dominance

The Treaty of Allahabad in 1765 granted the Company the right to collect revenues in Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa. This increased the Company’s wealth significantly.

Permanent Settlement

To increase revenue and control land, Lord Cornwallis introduced the Permanent Settlement system, making landlords responsible for tax collection. This increased the Company’s revenue but also led to widespread poverty among peasants.

Maratha and Mysore Conflicts

The Marathas, who had recovered after the Battle of Panipat in 1761, were becoming a significant power. Meanwhile, in Mysore, Haider Ali and his son Tipu Sultan, with a French-trained army, posed a threat to the Company. Through strategic alliances and military campaigns, the Company managed to suppress these threats.

Lord Wellesley’s Policies:

In 1798, Lord Wellesley became the Governor-General. He aimed to counter Napoleon’s threat and eliminate French influence in India. By forming alliances and defeating local rulers, he expanded the Company’s control.

Defeat of Tipu Sultan

In 1799, the Fourth Anglo-Mysore War saw the death of Tipu Sultan and the end of Mysore’s threat. The Company now controlled southern India.

Maratha Wars

The Marathas, divided by internal conflicts, faced defeats in the Second and Third Anglo-Maratha Wars. The Treaty of Bassein in 1802 and subsequent battles saw the Company consolidating power in central India.

Decline of Mughal Authority

The Mughal Emperor Shah Alam II, under Company protection, became a figurehead. The Company now controlled most of India.

Financing the Plunder

The word “loot,” signifying organized plunder, was introduced into the English language from India. This plunder by the East India Company (EIC) was facilitated through lies, promises, deceit, threats, and warfare. The EIC’s operations were funded by the wealth they amassed and borrowed from Indian financiers. Prominent among these financiers were the Jagat Seths, Marwaris from Rajasthan who had relocated to Bengal to capitalize on the province’s prosperous trade under Mughal rule. Initially, these financiers faced challenges with local Nawabs, particularly Siraj ud-Daula. Their alliance with the EIC led to the downfall of Siraj ud-Daula, granting the Company control over the ‘Diwani’ – the state’s economy.

Subsequent Governor-Generals continued to raise capital and borrow from Indian financiers from regions such as Rajasthan, Banaras, and Surat to finance their military campaigns, notably the Anglo-Maratha and Anglo-Mysore wars. The EIC’s prompt repayment ensured the financiers were willing to support these wars, making it an ironic situation where Indian money funded Indian soldiers fighting against Indian rulers. The masterminds behind this financial strategy were, of course, the EIC.

The British never had to face bankruptcy or the need to finance Indian cotton, spices, textiles, or other goods out of their pockets. Instead, Indian financiers funded the Company, which then repaid these loans through exorbitant taxes imposed on the already suffering Indian populace. This cycle of exploitation effectively financed the EIC’s plunder of India, enriching the Company at the expense of the Indian people.

Economic Exploitation

In 1600, when the East India Company (EIC) was founded, Bengal was a powerhouse of economic activity, contributing 80% to the GDP of the Indian subcontinent. At that time, the Indian subcontinent accounted for more than 40% of the world’s GDP. Bengal’s wealth stemmed from its thriving textile industry, abundant rice production, and extensive manufacturing.

By 1750, the EIC was generating over $300 million annually, coinciding with Siraj ud-Daula’s rise to power in Bengal. However, within just twenty years, Bengal’s fortunes drastically reversed. The province faced severe decline, compounded by several failed monsoons, leading to widespread devastation. The death toll soared past ten million, and Bengal, once a prosperous province, was left impoverished and struggling.

Despite this calamity, the EIC’s Directors reported a remarkable increase in dividends from 10% to 12.5%, attributing it to their success in exceeding tax revenue targets. The Company had extracted immense wealth from Bengal, but this came at a severe cost. The province was drained of its resources, leaving its citizens in dire poverty and suffering. The EIC’s relentless exploitation transformed Bengal from one of the richest regions in the world into a symbol of economic ruin and hardship.

The Company’s exploitative policies and heavy taxation led to widespread discontent, culminating in the Indian Rebellion of 1857. This marked the end of the Company’s rule, and the British government took direct control of India, marking the beginning of the British Raj.

Conclusion

From a small trading company in London to a political power in India, the East India Company’s journey is a significant part of history. It highlights the impact of colonialism and the eventual rise of British control over India.

To learn more about History visit our History Section