Do you want to change your life for better ?? You might wish to eat healthier. You may want to read more books, learn a new language, or improve your guitar skills. Saying what changes you want to make is simpler than actually making and sticking to them. You will not necessarily eat more vegetables simply because you want to. Saying you’ll read more doesn’t imply that you’ll start reading Atomic Habits instead of watching Netflix all night. However, habits come into play here. We’ll discover together that the key to making significant changes in your life doesn’t necessitate enormous turmoil; you don’t have to completely alter your behavior or who you are. Instead, you can make little modifications to your behavior that, if repeated, will develop into habits that will help you achieve larger goals.

Table of Contents

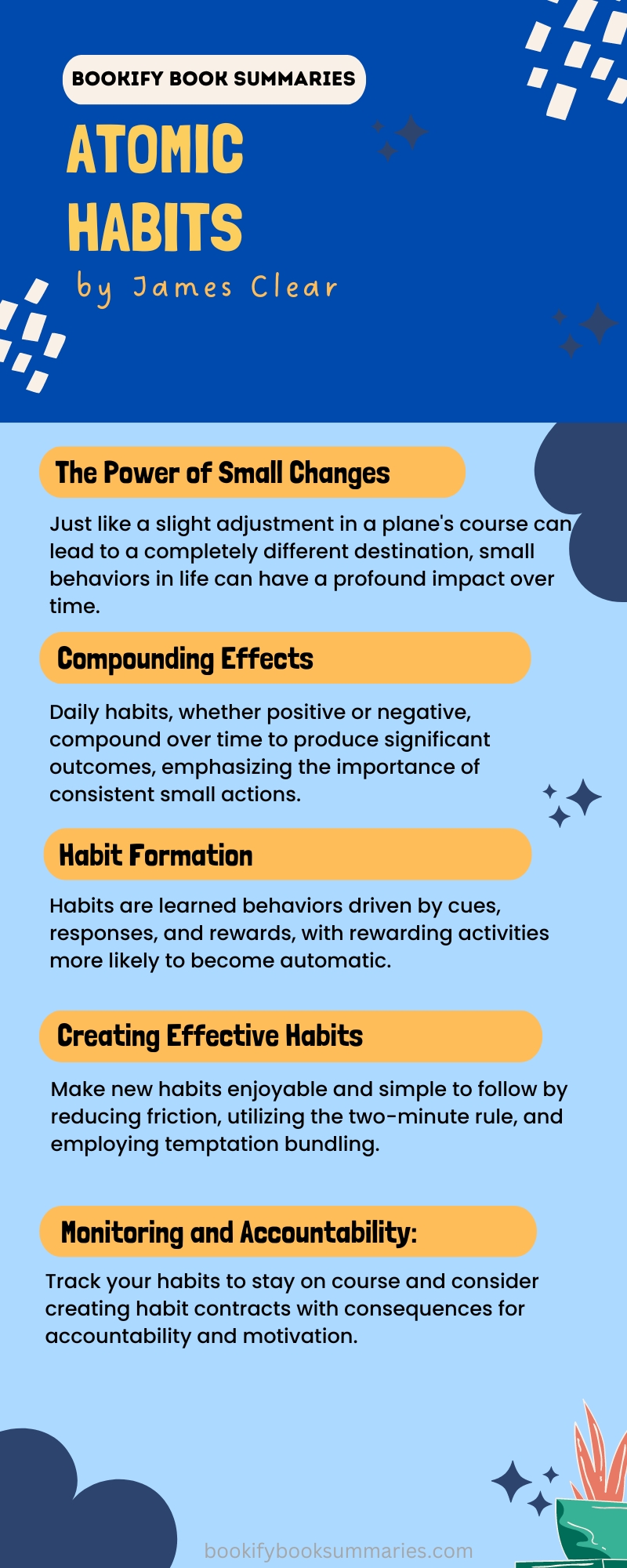

ToggleEven little things can change your life.

Envision a plane preparing to take off from LAX. New York City is the plane’s final destination. After the pilot has entered all of the necessary data into the jet’s computer, the plane sets off in the right direction. Just imagine for a second that the pilot makes a small errand just after takeoff and alters the plane’s direction. A mere 3.5 degrees, or a few feet, is all he shifts it. Neither the pilot nor the passengers seem to notice the little slant of the plane’s nose.

But this little adjustment would significantly impact U.S. interstate traffic. Instead of New York City, the pilot and his confused passengers would reach Washington, DC at the end of their voyage.

The simple things that happen in our lives go unnoticed. Tiny adjustments don’t make much of an impression right away. Jogging for 20 minutes will not help you get in shape if you’re already not in good form. Have dinner on the house and you won’t put on weight in a day.

But if we do these little things every day, our choices add up to big changes. You may expect to put on quite a few pounds if you consumed pizza on a daily basis for an entire year. Jogging for 20 minutes daily will lead to progressive weight loss and improved fitness, even if you don’t see a difference right away.

We know it’s disheartening when your hard work goes unrewarded. If this is happening to you and you’re feeling discouraged because you don’t see any positive change happening right now, try to concentrate on where you are in your journey instead of where you are right now.

For example, suppose your bank account is really low. However, your monthly savings are growing. Your present earnings might not be spectacular, and your savings is still not very large. Nonetheless, you might be sure that you’re on the right track. If you stick to this routine for at least a few years, you should see significant results. If you’re feeling down about your progress, just remind yourself that you’re doing everything right.

You naturally want to find the light switch the second you step foot in a room that is dark. The motion of reaching for a light switch has become automatic due to your repeated practice.

This kind of habit permeates every aspect of our existence, from driving to tooth brushing. They have a lot of power.

But how do routines become habitual?

Edward Thorndike, a psychologist from the 1800s, attempted to tackle this very issue. He started by putting some pets into a shadowy container. Then he kept track of how long it took them to run away. The first thing that stood out was how each cat acted when put in a box. In a state of panic, it looked for an exit. It probed the edges, snuffled, and scratched the walls. The cat managed to find its way out of the room by pressing a lever that unlocked a door.

After Thorndike rescued the cats who had escaped, he went through the same process again before putting them back in the box. Exactly what did he discover? Each cat found the secret after trying it out in the box a few times. The cats skipped the brief exploration of their surroundings and headed directly for the lever. The typical feline was able to get away in six seconds after twenty or thirty tries.

Put simply, pets had gotten into the habit of escaping from their cages.

A major takeaway from Thorndike’s experiment is that people are more inclined to repeat actions that have a favorable outcome, like getting more freedom, until they become second nature.

We now know that there are four main parts to a habit.

To begin, there is a signal or reason to take action. Entering a room that is completely dark forces you to take a step that enables you to see. The next step is to change the state, namely from dark to light. After that, there’s an action, like flicking a switch to turn on the light. As with any habit, the reward is the last stage on the road to success. Here, it’s the sense of calm and contentment that comes with being able to take in your immediate environment.

The process by which all habits work is identical. Morning tea, is it a daily ritual for you? When you wake up, you realize you need to pay attention. The thing you should do in reaction is to make some tea and get out of bed.

Feeling revitalised and prepared to take on the world is your reward.

Transformative behavior change necessitates measurable outcomes and deliberate strategies.

You can shape the process of habit formation to establish positive, long-lasting habits once you know how they function.

Consider how much you want to master the guitar. You have the necessary equipment and have mastered the basics, but you find it difficult to maintain a regular practice routine. No matter how many times you tell yourself you will play later, you never even get around to picking up your guitar.

You may put your newfound knowledge of habit formation to good use, though. Here, it’s important that the signal to grab your instrument be crystal clear. Put your instrument in the middle of the living room, where it will be easy to see, rather than a cupboard or a spare room corner. To make exercising a habit out of a desire, set a clear and obvious cue.

Altering your surroundings to better highlight your clues is helpful, but implementation intentions can take your triggers to the next level. So, describe them.

Most of us aren’t specific enough when we say we want to start a habit. We make statements like, “I’m going to learn to play the guitar,” or “I’m going to eat better,” and then we cross our fingers that we actually do these things.

To get over the unclear objective, an implementation intention can be useful. Making a specific strategy for when and where you will engage in the habit you want to cultivate is what an implementation intention is all about.

Returning to our guitar example, I understand. Prompt yourself with specific days and times when you will practice guitar. For example, instead of saying, “You’re going to practice guitar sometime this week,” commit to practicing for one hour on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday. Remember to leave your guitar in the middle of the room.

You might be surprised at how much easier it is to establish a healthy habit after you set an implementation objective, which gives you a clear plan and an evident hint.

Is it effective, though, even though it all makes sense? Am I able to alter my surroundings in a way that facilitates the development of positive routines? This looks fantastic in writing, doesn’t it? However, in actuality, what takes place?

Here we have the work of a Boston doctor named Anne Thorndike, who is unconnected to the cat-loving Edward Thorndike. Helping her patients develop healthier eating and snacking habits was a common goal for Dr. Anne Thorndike. The fact that it may be difficult to make a deliberate choice to eat better was something else she was cognizant of. Being self-disciplined and having strong willpower are two qualities that not everyone possesses in abundance.

This led Anne Thorndike and her team to develop a test. The initiative included her rearranging the hospital cafeteria. Aside from scattering bottled water baskets about the restaurant, the soda dispensers at the registers had their drink restocked with water. As for Dr. Thorndike and his colleagues, they patiently awaited the outcome.

So, in your opinion, what transpired? Soda sales dropped 11% over the course of three months, while water sales surged by over 25%. More signals encouraging people to drink water were all it took for Dr. Thorndike and her colleagues to succeed in getting people to do it.

To rephrase, they helped people adopt healthier habits automatically, without requiring them to consciously choose to do so. The research is clear that a change in surroundings can aid in the development of improved behaviors.

Keeping to routines becomes much easier when you incorporate elements of intrigue, as the promise of a reward is a powerful motivator for people.

Our investigation on Atomic Habits is currently in its midpoint. We have discussed the importance of habits, their formation, and the strategies for capitalizing on habit cues.

Rewards:

To better understand the neural bases of desire, neuroscientists James Olds and Peter Milner performed an experiment in 1954. They managed to prevent certain rats from releasing dopamine by means of electrodes. Surprisingly, the lab rats just lost interest in continuing to live. Dopamine is essential for their survival; without it, they would not feed, drink, reproduce, or do anything else. They succumbed to dehydration just a few days down the road.

Dopamine is an excellent motivator, as this terrible tragedy shows us. Eating, drinking, and having sex are all things that contribute to our survival, and when we do these things, our brain releases dopamine, which makes us feel good. Feeling good about yourself encourages us to keep doing what’s working.

All is well thus far. However, what does this have to do with the formation of habits?

To acquire a dose of dopamine, we don’t even have to perform something fun. Just thinking about performing something pleasurable triggers the release of dopamine. Wanting something is the same as getting it in the brain’s reward system!

This is an opportunity that we can seize. If we can make a new habit out of something we enjoy doing, we are more likely to keep at it.

I’d like to explain the idea of temptation bundling to you now. When you mix two behaviors that you like but don’t particularly like, you’re engaging in temptation bundling. This is the secret to harnessing the power of dopamine to establish a new habit.

Take Irish engineering student Ronan Byrne’s tale as an example. Ronan was aware of the importance of exercising more, but he hated going to the gym. He did, however, take pleasure in his Netflix viewing. Ronan dismantled a stationary bike. By linking the bike to his laptop, he was able to program it to only play Netflix content at specific speeds while he cycled. By associating physical activity with a habit, he turned a chore into an enjoyable experience.

To use this in your life, you are not required to create an intricate Netflix/exercise bike hybrid. Other, less complicated approaches exist. If you’re a gym rat who can’t resist perusing the newest gossip about your favourite celebs, you might resolve to read nothing but magazines as you work out. When you reach your tenth prospect, carve out half an hour to watch ESPN if you’re a sports fan who needs to listen to sales calls.

To receive a dopamine rush and form good habits, all you have to do is figure out how to make those boring but essential jobs more fun.

Make it as simple as possible to stick to your new habit if you wish to start one.

One method to make a habit last is to make it enjoyable. We can also facilitate the process of habit formation.

Even the smallest actions have a profound impact on our lives. Because they are easy tasks, we engage in social media and snack on potato chips. But learning Mandarin or doing one hundred push-ups are both challenging and time-consuming tasks. Because of this, we don’t feel compelled to engage in strenuous physical activity or study a foreign language when we have free time.

The chances of our preferred behaviors becoming habits are higher if we make them as easy as possible. Many more options exist for accomplishing this, which is great news.

Keeping resistance to a minimum is the initial strategy. Let me explain what it means.

When it comes to sending out greeting cards, James Clear has never been good. But his wife will never pass up an opportunity to send a greeting card. For this, there is an obvious reason. At her house, she keeps a box of greeting cards organized by event. With just a little bit of planning ahead of time, you may easily offer condolences, congrats, or anything else that may be necessary. There is less hassle involved with sending a card because she doesn’t have to run out and get one every time someone gets married or starts a new job.

There are two directions in which friction can act. In the same way that you can raise friction to break a bad habit, you can decrease friction to develop a good habit.

Simply turning off the TV and removing the batteries from the remote will allow you to spend less time in front of the screen. By increasing the level of difficulty, you may be sure that you will only watch when you are truly interested.

Thus, that is conflict. The two-minute rule is the second strategy for long-term habit ease. If you want any new endeavor to seem doable, this is one strategy. We can reduce any action to a habit that requires no more than two minutes of your time. Therefore, reading a book per week is not going to get you much reading done. Alternatively, commit to reading at least two pages every night.

Another option is to wear your running gear daily after work if you intend to run a marathon.

A method for creating habits that are both manageable and attainable, the two-minute rule suggests starting with smaller goals and working your way up to more ambitious ones. As soon as you slip on your running shoes, you’ll probably hit the pavement. It is highly probable that you will proceed after reading two pages. Just starting is the first and most critical step in finishing a task.

In order to successfully change your behavior, you must make your habits engaging at first.

We are almost at the end now. However, before we proceed, let’s go over the last guideline for improving your life through routines. We require a narrative in order to achieve this. This is the life and work of the late, great public health researcher Stephen Luby.

While employed in Karachi, Pakistan, in the ’90s, Luby achieved professional success. His efforts resulted in a 52% decrease in cases of diarrhea in indigenous youngsters. In addition, he reduced skin infections by 35% and pneumonia by 48%. This soap was the key to Luby’s huge success in public health.

In order to decrease sickness, Luby understood that fundamental cleanliness practices, such as washing one’s hands, were crucial. The general public also noticed this. But they weren’t committing their newfound information to memory. The turning point came when Luby collaborated with Procter & Gamble to provide the community with free, high-quality soap. Overnight, washing one’s hands became a pleasant ritual. I loved the new soap’s wonderful scent and how well it lathered. Since washing one’s hands was a fun and relaxing exercise, everyone joined in.

Last but not least, habits need to be pleasurable; Stephen Luby’s experience shows this.

Deciding how to make doing good things fun could be challenging. Human evolution is to blame for this. Our current reality is characterized by delayed returns. You show up for work today, but you won’t get your money until the month’s end. Going to the gym first thing in the morning won’t magically lead to a loss of weight.

Regrettably, our minds have adapted to a world where there is no delay in responding. Prompt adherence to a diet plan or money for retirement were not priorities for our ancestors. Things like finding food, finding a place to hide, and staying vigilant enough to avoid saber-toothed tigers were high on their list of priorities.

This tendency toward seeking pleasure immediately could lead to the development of bad routines. Although smoking may lead to lung cancer in the long run, it provides temporary relief from stress and satisfies nicotine cravings. You should probably ignore the long-term health risks associated with smoking because the short-term effects are more important.

Do your best to associate some immediate joy with actions that will have a delayed benefit; this is all it really implies.

The author’s personal experiences with a couple she knows will help to clarify this. They wanted to save money, eat healthier, cook more at home, and eat less out. Achieving these objectives will take time. A “Trip to Europe” savings account, to which they added $50 for every day that they forwent eating out, gave them an immediate boost to their objectives. The short-term rush of excitement from seeing $50 appear in their savings account kept them motivated for the long haul.

Make a system out of contracts and monitors to keep your actions in check.

Alright, we have mastered the art of habit formation. But sometimes we just can’t seem to stick to our habits, no matter how much we enjoy them. Therefore, in this last blink, let’s try to keep our good intentions.

Developing new habits that last might be as easy as keeping track of your habits.

A lot of people have been successful in the past because they kept track of their own actions. There are few people as famous as Benjamin Franklin. At the age of twenty-one, Franklin began keeping a journal in which he detailed his commitment to thirteen principles. Among these principles were the goals of never engaging in pointless argument and consistently making a positive contribution. Franklin would check in on his progress in each area nightly.

Franklin recommended keeping a simple calendar or notepad to record the days you adhere to your chosen habits. This is a great way to put Franklin’s advice into practice. Because habit monitoring is both enjoyable and beneficial, you will find it useful. You will be thrilled and driven by the anticipation and action of crossing each day off your list.

Disincentive for antisocial conduct:

The Nashville businessman Bryan Harris was very serious about his habit contract. He and his wife and trainer made a pact to lose 200 pounds. In order to get there, he decided to adopt a few behaviors. Meal tracking on a daily basis and weekly weigh-ins were part of this. Subsequently, he instituted consequences for falling short of these objectives. He was in danger of losing $500 to his wife if he failed to weigh himself regularly and $100 to his trainer if he failed to report his food consumption.

His fear of embarrassment in front of two very important people, as well as his fear of losing money, drove the approach to success. In the end, we are social beings. We value the thoughts and feelings of people close to us; the mere awareness that someone is observing can serve as a strong incentive to excel.

Consider establishing a habit contract. Think about pledging something to your significant other, closest friend, or colleague, even if it’s not as extensive as Bryan Harris’. Sticking to your program will be much easier if you and your partner agree on a set of consequences for failing to follow through. Plus, as we’ve seen, the key to a successful life is building good habits, no matter how tiny.